From Cheesemaking to Child Migration: What Tracing My Maternal and Paternal Lines Uncovered

Two of my earliest genealogy research goals were to trace both my direct maternal and paternal lines as far back as I possibly could. This led me to discover so much about several ancestors in the process, not just direct line relatives. But two stories from my direct lines stood out to me in particular. One led to a fun little aha-moment, while the other uncovered a life story of struggle and resilience.

So let’s learn about the stories of my second-great-grandparents, from different sides of my family, from different parts of the world, living very different lives.

Enjoying these insights into my family tree? Check out this story of how an unexpected pregnancy led my great-grandmother’s family to immigrate to Canada.

Let’s Get Cheesy: How I Discovered an Ancestral Love of Cheese From My Great-Great-Grandfather’s Obituary

It only took going back a few generations to learn something pretty cool from the Macdonald side of the family. It was something that I had never questioned before: where my love of cheese came from.

A great way (my favourite way really) to learn personal details about an ancestor is by reading their obituary. Obituaries often include facts that you wouldn’t learn from vital statistics — things like organizations they volunteered with or hobbies they dedicated a lot of their time to.

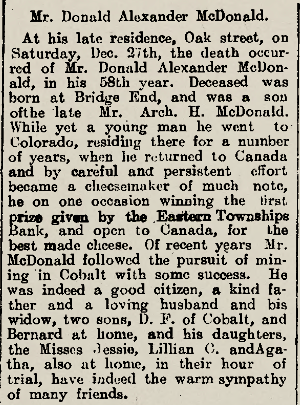

I was browsing over my second-great-grandfather Donald Alexander MacDonald’s obituary when a certain detail caught my attention.

Published in the local paper, The Glengarry News, Donald’s obituary mentioned that he was an avid cheesemaker who at one time won a nation-wide contest for his glorious cheese. I connected to this immediately. My entire Dad’s side of the family loves cheese. And when I say we love cheese, I could live off of cheese without hesitation.

It was a cool surprise to learn that for generations — literally — cheese has been a part of my family’s lives. It was especially surprising since other records like censuses had listed Donald as a farmer or miner depending on where the family was living at the time. But there had never been anything recorded to indicate that he made cheese or specified if he was a dairy farmer.

I wanted to find out more about this competition and my grandfather’s cheesemaking. I actually contacted a Canadian cheese historian to see if she knew anything about this. Unfortunately she didn’t know about the specific contest, but gave me lots of amazing information about small-scale cheesemaking in eastern Ontario at the turn of the 20th century, painting the picture of Donald’s daily life.

One brief but noteworthy mention of being a cheesemaker rounded out the image I had of my ancestor. Other records made him out to be a tough, strong working patriarch, but here I learned about this artisanal touch that seemed to bring his personality to life.

The British Home Children: My Ancestral Family Torn Apart in the Name of a Better Future

I was lucky enough to know my great-grandmother. I spent a lot of time with her when I was young, and loved to ask her what it was like growing up in the 1920s and 30s. She was one of my older relatives who fostered my love of learning about those who came before us.

She also liked to tell me about her parents — specifically her mom, Alice Unwin. She, along with her two sisters, came to Canada as British Home Children. She told me that her mom had to leave her sisters to live with another family on a rural farm who adopted her. She loved her time with her adoptive family, but never really told my great-grandma about her life in England. She stayed in touch throughout her life with her eldest sister, but lost touch with her middle sister.

This always stayed with me. How could little kids get onto a boat without their parents, be cared for by strangers, then be completely separated to go live and work on farms? Of course, these were very different times. This was seen as the best way to help these unfortunate children.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, over 100,000 impoverished and/or orphaned British children were sent to Canada to work as farm and domestic labourers. They were called “Home Children” because they typically entered some kind of charitable care home in Britain before emigrating, and then were received by charitable homes which housed the children before they were permanently placed with Canadian families, mostly on farms.

As an adult, my great-grandmother wrote to the organization that held the Home Children’s records in Britain to learn more about her mother’s time in their care. I recently learned from my grandmother (Alice’s granddaughter) that Alice’s file included that her father was not present in their lives, and that her mother was seriously ill with tuberculosis. My grandmother couldn’t remember much else, since the actual records that my great-grandma had received decades ago had been lost. This just made me want to find out as much as I could.

Many people have the impression that Home Children were mostly orphans. However, the majority of these children had living parents who either voluntarily left or forcefully had their children placed in the care of a charitable home as a result of living in very poor conditions in industrial Victorian England.

In the case of my ancestors, it’s still unclear if Alice’s mother had died by the time the girls left for Canada. By the 1901 census of England, the girls were living as boarders with an older woman and her adopted adult daughter. Their birth places were listed as “not known” and no other relevant information was listed. I also have yet to confirm if their father was living or dead while his daughters were in the care of various people — I’m still not even sure about his first name.

Two of the girls, Alice and her eldest sister Margaret, were sent to the same receiving home, the Hazelbrae Barnardo Home for Girls in Peterborough, Ontario. The two stayed in touch throughout their lives, having their families vacation together as late as the 1960s. It does sadly seem that their other sister Annie did not stay with them and I haven’t found any evidence of their lives overlapping again.

Margaret, left, and Alice, right, c. 1940

The Unwin sisters’ paper trails in Canada and later the US revealed some answers, but also left me with more questions. The three sisters all had different first names listed for their father on their marriage licenses. They wrote their mother’s name as Elizabeth or Eliza, but were inconsistent regarding her last name.

Right now, this branch of the family is under what I like to call “active research.” Some time and patience will be required, but I'm sure I'll be able to break past this brick wall. Since I’m looking at three sisters, using strategies like doing collateral research will be key to learning more about the Unwin family, especially their mother Eliza(beth).

I've had a great time chatting with my grandmother recently about what she already knew, and I'm so excited to see what else I can find out about our common ancestor Alice Unwin, and her relatives.

The Importance of Oral and Recorded Histories

Tracing my direct maternal and paternal lines have left me noticing some cool similarities and differences between these two sides of my family.

Most of my older relatives on the Macdonald side had passed away by the time I even started researching my family tree, so utilizing records and DNA have proven to be the most useful strategies on that side. But it seems to be the opposite for my maternal line — which is more common than you think when it comes to female ancestors.

Women have been historically viewed under the authority of a man, either her husband or father (and sometimes even a brother if the former two were already deceased.) This means seeing records that reference a female ancestor without ever using her name (e.g. Mrs. John Smith.) The paper trail for women often has gaps that we have to fill in, and this is where stories passed through generations become so meaningful.

Even though records have been lost to time, my grandma knows the story of her grandma, and is able to share it with me. And maybe someday, I’ll get to share these stories with my own grandchildren.

Do you have any fascinating stories in your family tree? I’d love to hear them in the comments below!